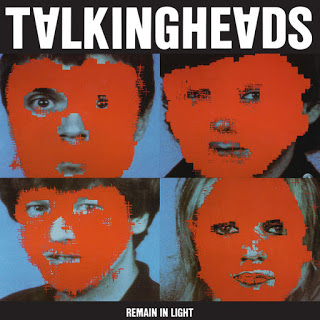

I could write a whole book about this album, and I just might because I’m in the mood to alienate my loyal fanbase of two (me and my imaginary cat). I will also be so bold as to announce that this review may end with the final score of “EXCELLENT” displayed in fanciful rainbow font, thereby breaking and urinating right on top of the system that I had painstakingly upheld thus far. To hell with burying the lede, Remain in Light deserves to be brazenly lauded as one of the finest rock albums ever made right here in my very first paragraph. That’s the stance I’m taking and I’m sticking to it. And I’ll go into an OCD-fueled conniption fit if I really do plaster a rainbow “EXCELLENT” at the end, so I’ll avoid that and you’ll all have to settle for a paltry green “Very Good” instead.

One of the more staggering tidbits of information you don’t see around much is that the Heads “took some time off” between their Fear of Music touring and returning to the studio for pre-production planning on the new album. In this day and age, when most hard-working musical groups and artists average about two or three years between albums, one would expect a rather significant hiatus if an action as deliberate as “taking time off” was considered. In fact, the four members of the Talking Heads took off three piddly months. Byrne spent time working with Brian Eno on their ongoing My Life in the Bush of Ghosts collaborative album. Harrison produced a Nona Hendryx album. Frantz and Weymouth took an extended Caribbean vacation, mingled with the locals, participated in Haitian religious ceremonies, and rubbed elbows with Sly and Robbie in Jamaica. I’ve spent entire summers home from college playing video games and watching TV, so just the mere thought of spending “time off” doing activities that don’t sound at all like taking “time off” is perplexing and infuriating to me.

It wasn’t all lollipops and sweet, sweet Jamaican ganja, though. Franz and Weymouth spent a lot of this time deliberating over dropping out entirely due to their dissatisfaction with Byrne’s tendency to micromanage and overpower the democracy established by the band in the first place. Byrne apparently agreed with this and mumbled something in Asperger’s Latin about “sacrificing egos for mutual cooperation”. Harrison must not have cared one way or another. At any rate, maturity prevailed and compromises were made to allow for a more genuinely collaborative approach during the initial stages of Remain in Light‘s production. If the narrative of “disgruntled band sets aside differences and pulls it together to make the best album of their career” sounds familiar, a little-known band of nerds called The Beatles had done it with Abbey Road a little over a decade prior. Not that anyone is in any position comparing the Talking Heads with the Beatles, but hey, at least the Talking Heads had a woman in the band instead of a Ringo.

The grand vision for Remain in Light was to create an album that seamlessly fused Western rock music with African music, especially drawing upon the work of Nigerian Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti, and using Fear of Music‘s “I Zimbra” as an inspirational launchpad. Music was the focus first, lyrics came later. The Heads recruited Eno again to help produce the record and, of course, load it up with bleeps and bloops (and contribute on bass and keyboards when applicable). Most of the album was recorded during freeform, casual jam sessions with the four base members plus a small troupe of additional musicians (including Adrian Belew) and then assembled piecemeal in post. And without personal computers and sophisticated software to make this an easy feat, relatively speaking, the end product is even more incredible. We’re talking a literal analog cut-and-paste job here, a significantly more mind-numbing task than taking 529 Polaroid shots for the More Songs About Buildings and Food album cover! In the end, I wouldn’t call this whole endeavor of “seamless fusion” a total success considering the ’80s electronica with 40 years of hindsight diminishes the intended effect according to mine own two ears, but I’ll be FUCKED, FUCKED, if I didn’t believe that they created a completely unique sonic experience. No other album in existence sounds like this one, with it’s rollicking and unrelenting dance-funk/post-punk marriage polished rough-grit and glossed over with a mechanical sheen. The warmth of both traditional rock and roll and upbeat, polyrhythmic African music is undermined by the inclusion of cold, robotic machinery but not to the point of sterility. This is a critical point, because the ’80s was an era saturated with over-produced computerized emotionless nonsense. Eno scaled it back just enough to still retain the humanity, and it comes through without any perceivable effort. I can’t imagine how hard this must have been to accomplish.

The lack of complete homogeneous synthesis between the two styles is inconsequential anyway and should take a backseat to the mood established as a whole, which is dead on point. So who gives a shit either way as long as it works? Take the first three tracks, “Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On)”, “Crosseyed and Painless” and “The Great Curve”, three of the most exhilarating and consistent tracks to ever be consecutively placed on an album in history. The sheer, unrelenting energy alone over the span of these 17-odd minutes is enough to give them their high marks and be done with it! But I’m above that! That’s slacker talk and I plan on writing 12,000 more words! Among these three songs the repetitive rhythms sound tribal, but the electronic flourishes sound urban and industrial. Aha! The urban jungle! Throw in a nervous Byrne panting and yelping out cryptic lyrics and you’ve got a perfect musical metaphor for the individual’s experience of the hustle and bustle of modern megalopolitan sprawl. On top of that, you’ve got the tribal rhythms representing the pre-developed world at odds with modern societal expectations and constraints. On top of that, you’ve got Byrne playing the philosopher trying to intellectualize his way out of a situation beyond his control. Good God, I could go on and on. Without getting too specific on the minutiae of the first two tracks, “Born Under Punches” is an extremely veiled song where our neurotic protagonist is trapped in the throes of government heat “(The Heat Goes On!)”. “Crosseyed and Painless” ramps up the stress even further to the point where our neurotic protagonist can’t even trust reality (“Facts all come with points of view/Facts don’t do what I want them to/Facts just twist the truth around“). The best part is the uneasily calm chorus that starts with “There was a liiiiiiine/There was a formulaaaaaaa“, as if the song is pretending that everything is just dandy. I’ve been talking about the Talking Heads’ penchant for the paranoid throughout their whole discography so far, and we’re at peak anxiety here. There’s so much energy it’s begging to be neutralized. It’s truly a mesmerizing aural experience that deserves to be heard to be believed.

I would be remiss if I didn’t delve a bit deeper into “The Great Curve”, though, which tops the list of my favorite songs in existence any day. It probably even tops the list of my favorite things in existence, a list which also includes pixie cuts, the SNES game Earthbound, Fox Mulder, and I SUPPOSE my wife and child. I mean, come on, we’re talking layer upon layer of polyrhythmic action with a driving, perpetual guitar and bass call-and-response parlance and a seemingly never-ending supply of fluidly interweaving vocal sections. Also throw in a couple of crunchy-as-fuck guitar solos courtesy of Belew. Clocking in at nearly 6.5 minutes, I’d be ready, willing, and able to hang on to every note for an additional two hours. This song and its title are simultaneously about Mother Earth and women in general. Whether or not it’s a positive message on both is up to you to decide; far be it from these guys to not give every lyrical line a double (or triple, or quadruple) meaning. But the tumultuous nature (ha!) of the song’s otherwise steady-state condition could probably clue you in.

After the rambunctious blitzkrieg that was Side 1, Side 2 saunters in with a markedly more gentle approach with “Once in a Lifetime”, which surprisingly did not do well in the charts in the US (it hit #14 in the UK). I’m sure if MTV were actually around when the song came out it would be a different story, since they played the music video nonstop in its very early days. I’m sure you must have seen it at least once before, young reader–it depicts a suited-up and bespectacled David Byrne sweating and flailing around in front of a green screen. Byrne’s voice is back in the forefront after being hopelessly lost in the treacherous labyrinth of Side 1 while the rhythm chugs along as if there was nothing to fear in the first place. As great as this song is, it almost sticks out like a sore thumb amidst the high-energy freak outs of Side 1 and the gradual cooldown of the rest of Side 2. Don’t write it off, “Once in a Lifetime” has one of the most memorable chorus melodies of the pop-happy ’80s and the “THIS IS NOT MY BEAUTIFUL WIFE!” was a big ol’ meme long before memes were even a thing, or the Internet itself for that matter.

The rest of Remain in Light, the aforementioned “cooldown”, is just that: a series of tracks gradually dissipating the excess energy created earlier. “Houses in Motion” brings on the funkiest number since “Life During Wartime” with a bassline you could sink your teeth into, some spoken word passages, and a trippy, synthy solo to boot. “Seen and Not Seen” a gravely underrated and completely unsung bit of mild beat poetry (maybe beat prose?) delivered in Byrne’s trademark deadpan monotone cadence and washed over with garnishes of Eno’s synthesizer magic. Psychedelic music in its pure form. Most of the internet will rag on this one, I wholeheartedly disagree. Next up is “Listening Wind”, mellowing out even further with the flipside of the tribal coin. Gone by now are all remnants of the agoraphobic, urban lifestyle, with past heart-racing crises fading away into distant memories and replaced with subtle chirps of the real jungle–but stay on your guard. It’s still not safe. Finally, the weight becomes too cumbersome and crushes you underneath with the last gasp of breath on “The Overload”, a droning, introspective recap. The apocalypse is over now, the vast wasteland lies before you. Haunting in its breadth, I used to hate the shit out of this song because “ENO RUINS THE END OF EVERYTHING WITH HIS AMBIENT SHIT WAAAAHHH” (the end of David Bowie’s Low comes to mind immediately, bleehhhh), but I’ve come around on it in a big way over time. I can appreciate that even to the bitter end, even when the energy has dropped like a stone, they still funnel the anxiety from every possible nook and cranny.

Historical importance? Ooh baby. Well, for starters, Remain in Light topped many publications’ lists of the best albums of the 1980s, which means the ’80s had barely started and nothing as good would come out for at least 10 more years. It single-handedly made African music relevant and important to rock music and Western society in general (this one is sad, because it unfortunately took a group of nerdy white yuppies to accomplish this), paving the path for the big worldbeat boom that still finds its inspirations noodling out from indie rock and psychedelic rock outfits. It’s another nice example of artsy-fartsy smarty-pants aesthetics prevailing over meat-headed butt rockery (the fucking ’80s were full of that shit), effectively lighting the fire under the asses of other artsy-fartsy smarty-pants types who would go on to do great, successful projects themselves. The world always needs more nerd punks, I say. Plus, this is bar none the funkiest album ever put out by white people in history.

So, yeah, don’t be a dillhole about Remain in Light. Listen to it and love it like you’re supposed to.

Click here to ridicule this post!